Bandes On The Run

Tired of tussling with tentacles? New Swedish RPG The Troubleshooters offers a more light-hearted approach to the mystery genre. Luke Frostick grabs his passport and goes in search of adventure...

Tired of tussling with tentacles? New Swedish RPG The Troubleshooters offers a more light-hearted approach to the mystery genre.

Luke Frostick grabs his passport and goes in search of adventure with the game’s creator Krister Sundelin.

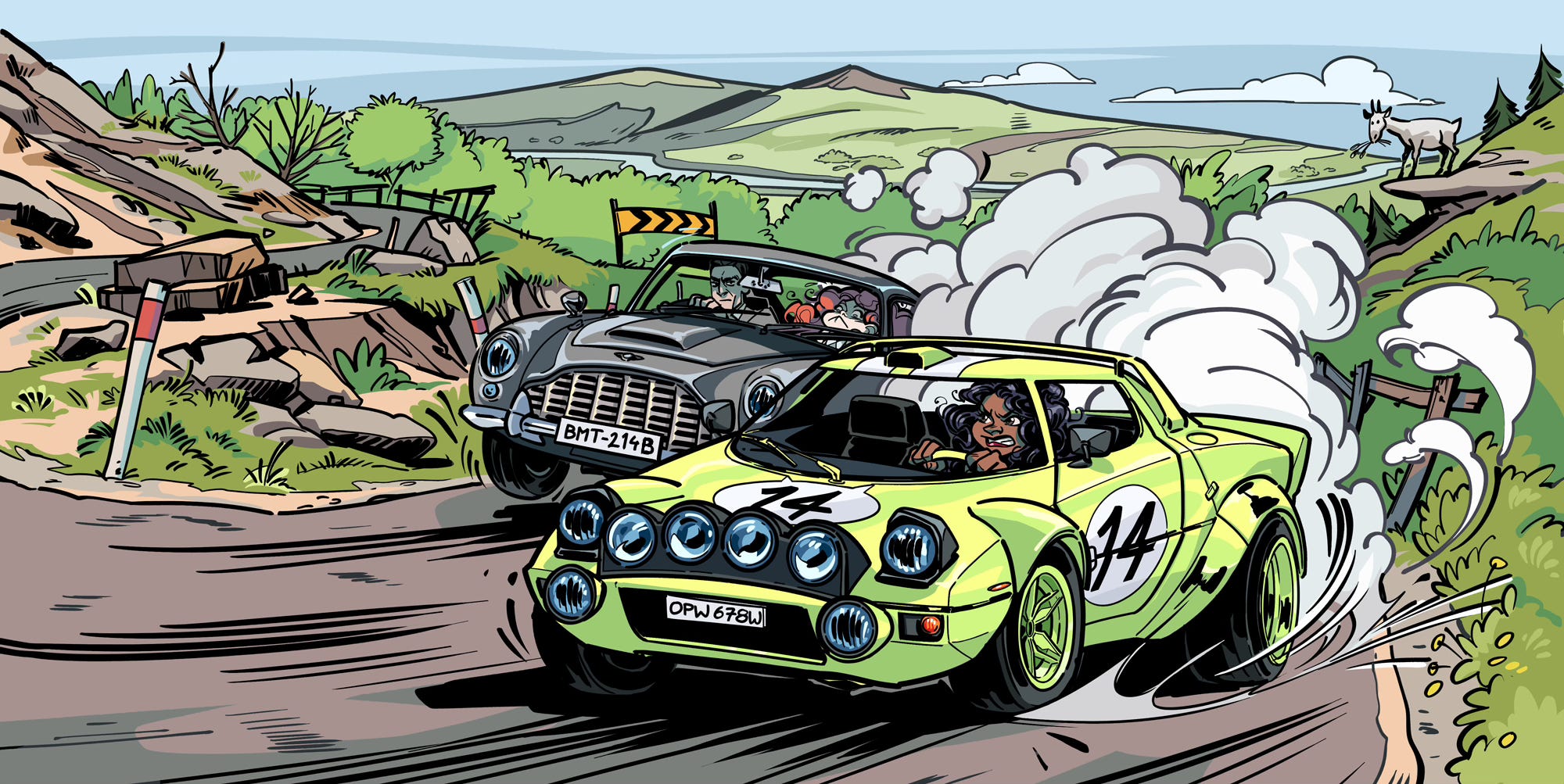

Art: Ronja Melin © Helmgast

Over the years investigations have often played a key part in our role-playing games, though generally speaking the focus has been on the threat of sinister cults in thrall to eldritch gods than the more glamorous possibilities a life of mystery offers. All that’s set to change with The Troubleshooters, a new RPG from Swedish designer Krister Sundelin.

A veteran of the Swedish RPG scene, Sundelin’s resume includes titles for publisher Helmgast such as iron age adventure game Järn and Hjältarnas Tid, an introductory RPG of epic quests for hidden treasures. Believing the fantasy genre to be ‘kind of crowded’ and always looking to try to create something new, Sundelin found inspiration for his new game in he colourful worlds of Franco-Belgian comics, or bandes dessinéess.

In Francophone Europe bandes dessinéess are very much a serious business, considered to be ‘the ninth art’, and a world away from the world of superhero and their capes. Whilst most English speakers will know of Hergé’s boy detective Tintin, bandes dessinéess encompass a vast range of genres and styles that, over the years, have ranged from saucy sci-fi strips like Barbarella to countless espionage thrillers and criminal cat-and-mouse capers.

‘I had a lot of Spirou books and I wondered why there wasn’t a roleplaying game for it. ‘Finally I got tired of waiting.’

It’s the latter of these, series like Yoko Tsuno and Spirou & Fantasio, that Sundelin initially turned to when he conceived The Troubleshooters. With the exception of a French language game based on the Valérian strip, Sundelin realised that wasn’t anything based on the comics he loved and the jet-setting adventures and criminal shenanigans their protagonists often find themselves involved in. ‘I had a lot of Spirou books and I wondered why there wasn’t a roleplaying game for it,’ he explains. ‘Finally I got tired of waiting.’

Taking further inspiration from the likes of James Bond, The Saint, Arsène Lupin the Third and The Avengers (the old, British, black and white spy show) and games like Call of Cthulhu, the old James Bond RPG, and even the Star Wars D6 game, Sundelin set to work and quickly found a home for the project with his old publisher Helmgast,

‘Two years ago I went to Helmgast and I showed them the first sketch of the cover,’ he tells me. ‘Everyone said, “Tell nobody about this. It is so good and simple an idea that everybody would steal it if they knew.’”’

It is easy to see why that initial sketch would provoke such a reaction from the Helmgast team. Ronja Melin’s cover art perfectly captures the style and the tone of euro comics. Likewise the interior art of the book is equally impressive and, in addition to just being beautiful to look at, does a lot of work establishing the feel of the game.

‘It doesn’t matter if you haven’t read anything from the source material,’ Sundelin says. ‘I think you could get what the game is about just by looking at the cover.’

“It doesn’t matter if you haven’t read anything from the source material. I think you could get what the game is about just by looking at the cover”

Sundelin describes Melin as a bit of a chameleon and shows me the illustrations she had previously done for Järn and Hjältarnas Tid which, whilst also beautiful, are in a completely different style.

‘When I asked her if she can do something in the French and Belgian style she said, “Why not?”’ he tells me and looking at the finished book Melin’s confidence was well deserved. Sundelin points to a French review of The Troubleshooters which laments how it was produced first by a group of Swedes and not a Frenchman.

That attention to detail permeates the book and Sundelin also highlights the work of graphic designer Dan Algstrand, how its clean lines, bold colours and use of specific typefaces, such as Le Monde, perfectly capture the feel of the game.

But it is not just the art and design that informs the tone but, importantly, the writing does too. Sundelin explains that he started off, quite simply, emulating the source material that originally inspired him and from there quickly realised that he wanted the game to be explicitly Eurocentric in tone. ‘Since most game authors are American, you get this very American feel to games even if they are not set in the US,’ he tells me.

Much like its source inspiration an important theme of the game is globetrotting or “fantasy tourism”. One of the reasons that people loved the Connery-era James Bond films was that back then a trip to the Caribbean or Japan was unthinkable for most bar the very wealthy. The same is true for comics like Tintin, whose adventures to exotic locations provided readers a vicarious thrill.

‘One of the things that Hergé and Roger Leloup [creator of Yoko Tsuno] had in common was that they were all subscribers to National Geographic and based their adventures on the latest issue,’ he explains. ‘I wanted players to sit down with the book and say “I want to have an adventure in Shangri-La. I want an adventure to go to Calcutta” or any place in the world.’

Another important aspect of Sundelin’s world-building that shines through in The Troubleshooters is its optimism. ‘I'm dead tired of grim dark games,’ he tells me and explains that the era he is trying to capture is ‘the period the French call the golden decades. It was a time when France was really modernising and building back up from the war. There was a positive outlook on the world. Even with the nuclear threat hanging over them, they were talking about the car of the future, space travel of the future. Everything was about the future and how bright it would be.’

That also helped Sundelin firmly establish the game’s era, as he didn’t want characters to be able to Google stuff, or get in touch via email. This decision was finally cemented though when he discovered that ‘the cars were just more beautiful in the 60s.’ It’s certainly hard to disagree on that point and Sundelin and I spend several minutes reflecting on just how very cool the Aston Martin DB5 is.

“The cars were just more beautiful in the 60s”

Regarding the setting’s era Sundelin tells me how he just missed out that era of optimism himself. Born in the 1970s his earliest memories were less those of a bright atomic age and more ones like the nuclear disaster at Harrisburg (Three Mile Island) and the referendum on nuclear power in Sweden.

Still, Sundelin does recognise that not all aspects of the 1960s can be defined as optimistic and adds that the prejudices of the era and some of the source material (looking at you Tintin in the Congo) did not fit into a game designed to be played in the modern world.

‘People can call that woke if they want, but I don’t care,’ he says. ‘I don’t want that in my game.’

Likewise he also takes certain liberties with the real history of the period in service of the game’s tone. For instance both the reality of both the Vietnam War and the Cold War are played down. They still exist, but he sees The Troubleshooters as being set in ‘that sobering up moment after the Cuban missile crisis.’

The tone of the game’s source material is also reflected in its rules. For all the high stakes car chases and shoot-outs death is not really a part of the game. Characters rarely, if ever, die and even the minions of the game’s perfidious criminal organisation, Octopus, are not killed when shot. They simply have their guns knocked out of their hands before falling into a convenient nearby body of water / bail of hay / puddle of mud.

The actual core mechanics of The Troubleshooters are based on those that Sundelin developed for Järn, a D100 system testing against skills. Whilst he has nothing against dice pool games, he explains how he doesn’t find them very intuitive and wanted a system that was both quick and very adaptable.

‘With a D100 system you know what the value is worth and can easily adapt to the situation,’ he says. ‘Especially when you are investigating, you have to come up with clues on the spot because it is not a dungeon. You have to improvise a lot. The intuitiveness of the D100 is very good for that.’

The other mechanic that Sundelin views as key to the game is its Story Points system. Essentially these are points earned for good roleplaying, roleplaying that might in some way disadvantage the player or the party. In turn these points can be spent to gain mechanical or narrative advantages such as your small but inquisitive dog finding a vital clue at just the right moment.

As an example he describes how if a character has the “honest” condition, they might gain a story point when they play into that and their honesty gets them in trouble. Likewise surrendering and getting captured rather than fighting to the bitter end might earn players a handful of story points which, in a fitting nod to the genre, can be used to escape from the jaws of certain death at the very last second.

‘I wanted a mechanic that allowed players to take control of the dice,’ Sundelin explains. He also wanted players to have the ability to directly change the game. ‘Basically because I see the game as more of a democratic conversation than the usual dungeon crawler. I want players to participate, to be creative and add to the story. So with the story points there is a legal reason to allow them to.’

“I see the game as more of a democratic conversation than the usual dungeon crawler. I want players to participate, to be creative and add to the story”

During the play testing of the game, Sundelin found that the economy around story points was a core feature that players latched onto, perhaps even more so than skills and they were often asking themselves how to ‘spend story points or get them from this scene?’

To maintain their central role, Sundelin had the number of story points refresh at the start of each session. He contrasts this with Force Points in the Star Wars D6 game which, as they did not refill, he found players never used. ‘What’s the point of a story point if you don’t use it?’ he asks.

By codifying how story points work and letting players know specifically how they can earn and use them, Sundelin believes this outsources the work of remembering them from the GM onto the players.

Whilst The Troubleshooters is quite mechanically heavy Sundelin believes that the systems that he included were necessary to encourage the kinds of play that he wanted to see and that he actually cut down the number of rules during development in a way he likens to the iterative design process used in the car industry. ‘If there is something you can simplify or some waste that doesn’t add to the mechanics, you get rid of it.’

Since its release the game has enjoyed a great response. Its first published adventure, The U-Boat Mystery, won silver in the Best Adventure category at last year’s ENNIE Awards and Sundelin has two more campaign books, The Great Champagne Galop, a Wodehouse-esque story about horrible relations, and The Ghost Knight, about a haunted castle somewhere in eastern Europe, in the works.

‘You need those books early on to get the game playable,’ Sundelin explains and also tells me how he would like to make an American adventure, one that shows how the US is seen from a European perspective. He is also working on some manuals and background books, in particular a major expansion to the setting’s villain, the criminal organisation Octopus.

Showing no signs of taking it easy he is also thinking of doing a book of boarding school mysteries along the lines of Swallows & Amazons or the Fantastic Five, another literary area notable for its absence in our games. Whatever comes next though, in a genre of most often typified by its nihilistic tones Sundelin’s exuberance and sense of optimism are a welcome burst of colour.