Standees In The Way Of Control

Tabletop games have often used fictional dystopias to, overtly or otherwise, critique our own world. But what happens when we ditch those fantasy and science-fiction analogues for the real thing?

Tabletop games have often used fictional dystopias to, overtly or otherwise, critique our own world but what happens when we ditch those fantasy and science-fiction analogues for the real thing?

Dan Thurot speaks to the designers of three games that haven’t shied away from putting historical events front and centre, confronting head on issues of race, gender and sexuality that continue to resonate today.

You’ve heard the refrain before: ‘Why does everything need to be all political? It’s a game! It’s supposed to be fun! Keep your politics out of games.’

Well I’m here to say that we need more politics in games.

If that quirks your eyebrows, I get it. ‘Politics in games’ conjures a particular image, one that’s dour and—dare I say it—rankles of ‘edutainment.’ It’s a natural response. Now that my kids are old enough to visit the library every week, they’ve become expert detectors of any book that’s trying to educate them on weightier matters than sharing, coping with emotions, or how the Dragon Prince of Wrenly will save his kingdom this week. Some part of our brain clamps down the instant it believes it’s being preached to.

To get a better sense for why politics belong in games, I spoke to three designers who’ve become known for their politically-laden productions. These designers hail from different backgrounds, genders, careers and lived experiences, but their commonalities are striking. They’ve all created celebrated commercial titles, have deep feelings about the value of play, and believe tabletop games can aspire to be more than fluffy children’s books for grownups.

Amabel Holland is a trans woman with well over fifty board games under her hat. Her designs are far-ranging, touching on train games both simple and complex (Northern Pacific, Irish Gauge, The Soo Line, Trans-Siberian Railroad), the historical (Supply Lines of the American Revolution, Nicaea, Westphalia, Endurance), and the whimsical (Eyelet, Watch Out! That’s a Dracula!), as well as many, many more than would be responsible to list here. Holland is famously open about her transition, including the scrutiny her sexual identity receives from strangers. In a time when transgender identities are subject to debate and legislation, it would be fair to say that her entire personhood has been politicized.

But Holland is no stranger to roiling waters. Long before her transition, she made waves with a design that seemed brash, even offensive. In 2018, This Guilty Land announced its intentions on its very cover. The central image is that of a man named Gordon, more commonly known as ‘Whipped Peter,’ his back horribly scarred by the lashings he received as a slave.

This photograph first appeared in a July 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, putting the brutality of slavery on display and inspiring free Blacks to enlist in the Union Army. There are thousands of board games about the American Civil War. Nearly all of them focus on operational deployments, orders of battle, the brother-against-brother conflict that still looms large in the American psyche.

Holland went another route: rather than preoccupying itself with formations of blue and grey uniforms, her game highlights the years leading up to the Civil War and the practice of slavery itself. Neither did Holland truck in ambiguity; in her game, players either embody Justice or Oppression, factional titles that leave little up to interpretation. Although she worked to ensure that slavery couldn’t be mistaken for anything other than evil, the thesis of This Guilty Land isn’t anything as obvious as ‘slavery is bad.’ Rather, it’s that moderation in politics is tantamount to joining the side of Oppression.

In This Guilty Land both sides of the debate are determined to swing a certain number of votes to their side of the legislative aisle. Justice, naturally, intends to abolish slavery. It’s a Sisyphean task, requiring its player to shore up voting blocs, change hearts and minds, and harden sentiments into political action. Even in a vacuum such a process would be difficult, but Justice is dogged at every step by Oppression. This player maintains the status quo by legalizing fugitive slave acts, launching campaigns of violence and voter suppression, and—this is the crucial part—keeping the nation’s moderates from voting the other way.

As a rhetorical statement, it’s a sobering one. Because slavery is already the law of the land, the Oppression player doesn’t need to legislate. All they need to do is prevent Justice from gaining enough traction to abolish the practice. This means that the tokens on the board that represent the middle ground, the undecided voters of the United States, are effectively votes for the continuation of slavery. Without directly confronting the player, This Guilty Land asks one of the toughest questions ever put to cardboard: In what ways do we, today, permit oppression by not standing for justice?

As someone whose mere existence has been politicized, Holland has plenty to say about the need for games to make such statements. It’s impossible to keep politics out of games, she argues, ‘Because politics touches everything. Politics defines our cultural norms and assumptions, and art—games included—either reflect or challenge those assumptions, and either do so obliviously or thoughtfully. Simply talking about the realities of my existence—as a queer woman, as a trans woman—makes the conversation “political.”’

In her estimation, to say that politics shouldn’t be in games is to adopt a position not unlike This Guilty Land’s moderates, where refusing to take a side always means siding with Oppression. ‘One thing I tried to be very clear with in This Guilty Land was that it wouldn’t give both sides equal footing,’ Holland says. ‘There’s a false idea of balance in our culture that sees objectivity as giving equal time and weight to both abhorrent ideas and to those that oppose them. The simple fact is that slavery was and is a moral evil on which there could never be any compromise.

‘I don’t give any credence to the idea that people didn’t know slavery was wrong, because people did. Some folks were dedicating their lives to end this thing, and it’s not like they failed to convince others—it’s that those others didn’t care. Either that’s a willful choice, or it’s being afraid to rock the boat, or it’s calling for civility and compromise and centrism and moderation. They’re villains or they’re cowards, and they choose to be those things.’

For Holland, this point is uniquely expressed via the language of play. ‘It’s about illustrating systems, both in terms of the creaky machinery of government, and also how civility culture and centrism—which is fundamentally a kind of conservatism, because like conservatism it abhors change and upheaval, no matter how necessary—works against progress.’

This is also why Holland deemed it necessary to ask players to not only embody Justice, but also Oppression. ‘It’s through the interaction [of factions] that these games communicate their meaning. This Guilty Land isn’t interested in the facile terror of “Here, play this bad person, do this bad thing, now feel bad, why did you do that bad thing?” I don’t think in playing one side or the other that you learn anything specific about that side. But by playing one side against another, the two of you observing these systems, that’s how you get something out of it. To foreground this observation, I tried to put a lot of distance between you and the roles you inhabit—making them abstract forces instead of specific historical entities.’

She’s also quick to caution prospective designers that tackling thorny historical topics is fraught.

‘How do I design around these topics? Very carefully. There are so many ways to get it wrong. You have to doubt yourself, constantly, on pretty much every aspect. You need to anticipate the questions people will ask about it, and the assumptions they might make. Just as importantly, you need to answer those questions before they’re asked. A year and a half before This Guilty Land came out, I was talking about what the game was and what the game was not, because I knew if I didn’t put that information out there, others would decide ahead of time what the game was, what the story was, and that would be disastrous.’

The effort, however, is worthwhile, because the issue isn’t solely academic. Holland draws a direct line from the moral weakness of permitting slavery to the issues under discussion today.

‘I’m a queer trans woman living in 2023 and my community is being legislated out of existence, and the people passing those laws are willfully lying. Don’t tell me they don’t know better; they do. They’ve been told over and over again what the science is, and they just don’t listen. Meanwhile, people try to play up both sides of a debate that doesn’t exist, or call for compromises when there can be none.’

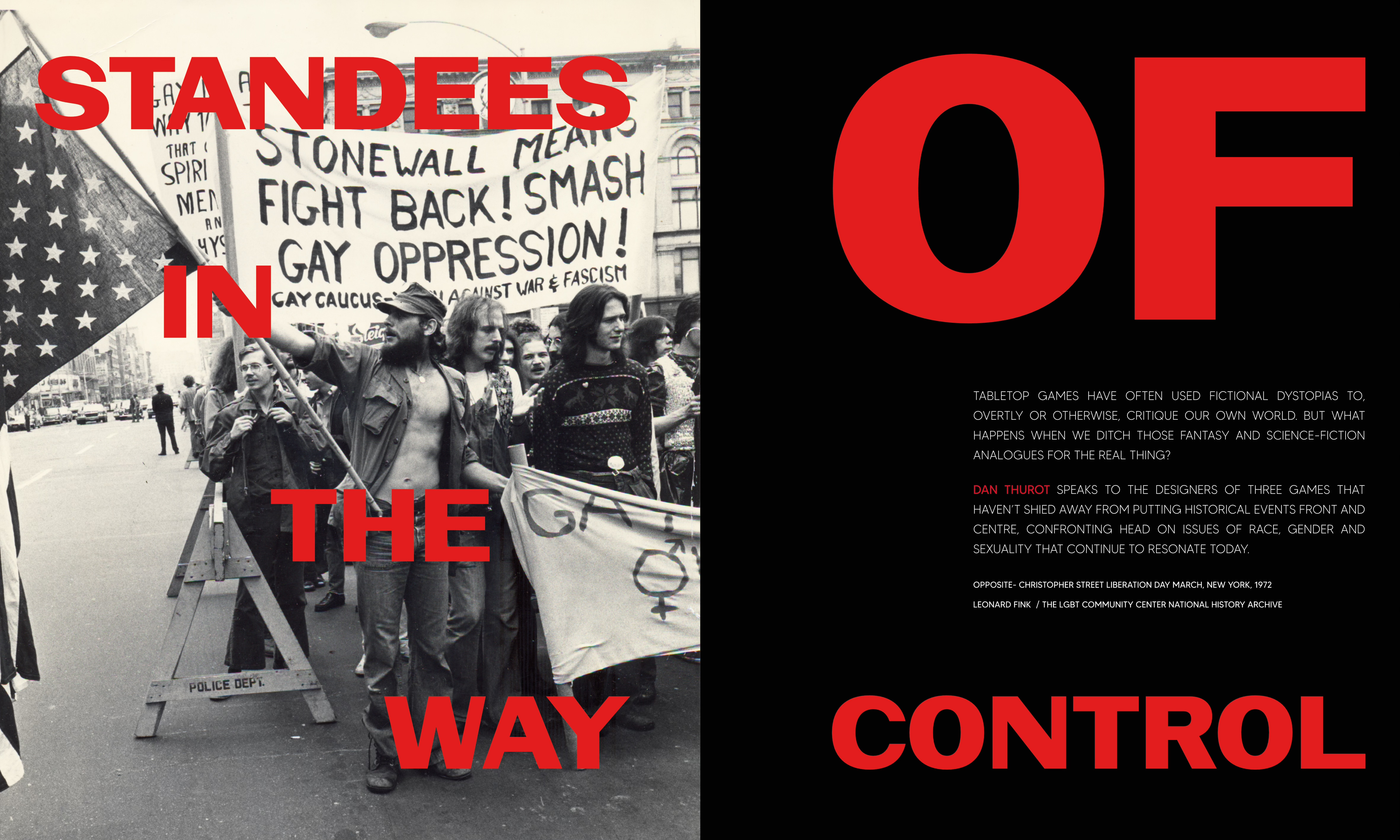

The impact of This Guilty Land has already been felt on tabletop games. Perhaps its most direct descendant is last year’s Stonewall Uprising, a design by Taylor Shuss that portrays thirty years in the fight for LGBTQ+ civil rights.

Stonewall Uprising is very nearly a mainstream game. Somewhat infamously, This Guilty Land was tangled and complicated, pitting players against the legislative system of the United States as much as against the opponent sitting across from them. This was a deliberate choice, highlighting how the same safeguards that prevent laws from being passed offhandedly can also impede the battle for equal civil rights. Despite being inspired by Holland’s game, Shuss settled on a well-worn core system: deck-building.

There are two sides to Stonewall Uprising, Pride and The Man, both with their own goals, but on a turn-by-turn basis they function according to familiar principles. Cards are purchased from a market, drawn at random into your hand, and eventually shuffled together again when your draw pile runs out. Anyone who’s played Donald X. Vaccarino’s Dominion or its hundreds of offshoots will find Stonewall Uprising intuitive.

But while Shuss felt it was important for his game to be accessible to a wide audience, he’s also keenly aware that its politics might catch some by surprise. ‘It felt important that players knew what kind of game they were stepping into when they held the box,’ he notes.

‘Stonewall Uprising is a game about queer history designed by a queer person. If that bothers you, feel free to play the other 99% of games that exist. Setting expectations was an incredibly important piece of the puzzle for us. We wanted to let players understand that the game is very much supportive of queer civil rights, but unfortunately the path we took here in the United States was not a terribly pleasant one, and still is not anywhere near perfect today, either. Showing off that level of seriousness is not an easy task without making the entire game look like a dour pit of despair.’

Shuss is referring to his game’s portrayal of The Man, his own analogue of the Opposition player from This Guilty Land. While Pride’s cards are vibrant and joyful, even somewhat cartoonish, The Man’s cards are bleak, with backgrounds crisscrossed by chain-link fences and shadowed illustrations full of angry faces. This prevents any misunderstanding—The Man is definitely the antagonist of the game—but the differences between in-game factions run more than ink-deep. Both sides also have their own victory conditions. The Man’s goal is all about imprisoning Pride’s cards, physically removing their presence and abilities from the deck. Meanwhile, Pride is all about amassing and rolling handfuls of dice in an effort to hit a moving ‘Overton Window.’ In other words, it’s Pride that gets to have all the fun.

Where This Guilty Land drew criticism thanks to what some perceived as an ungenerous portrayal of the antebellum United States, concerns with Stonewall Uprising had more to do with Shuss asking one player to control The Man. The final version of the game includes an automa that can take that role off players’ hands, letting them play solo against an impersonal foe, but from the beginning Shuss thought it important to let a thinking mind lead the charge against Pride.

‘I am aware of plenty of people that were put off by playing as The Man. That is definitely the number one piece of feedback I’ve gotten about the game. But ignoring that aspect of the conflict would be doing the game a disservice. While working on Stonewall, I made it a point that whoever is playing as The Man should feel at minimum gross while they are taking in-game actions. When you detain people, you tear them from Pride’s deck. When you demoralize people to win, you do so at random. And whenever you buy cards in the ’80s, AIDS deaths go up. These are all designed to make players feel a certain way. I think playing as The Man is more difficult than playing as Pride since you have to sit with the knowledge that what you are doing right now is wrong. You are oppressing people and the way you progress toward victory is vile.’

But why is it important for someone to inhabit such a difficult role? Shuss goes on. ‘The fact that The Man is played by a living breathing person makes their actions so much more tangible and hurtful. That a real person would willingly choose to go to such lengths to deny an entire group of people their pursuit of happiness, and still think that what they are doing is just or moral, is outright evil.’ Shuss also notes that in playtesting Stonewall Uprising, it was often those who played as The Man who emerged with the strongest feelings over the injustices portrayed in the game. ‘It puts their behavior in stark contrast to Pride, and draws clear lines around who and who is not on the side of justice and equality.’

When it comes to politics in games, Shuss has seen his own perspective develop over time. ‘For a time I had a similar opinion [that politics don’t belong in games]. Eventually I realized that that couldn’t coexist with me wanting to see more people included in the hobby I loved. Now I am of the mindset that all games are political, although often those politics are subtle and unintentional. These can still have some impact, so it is always worth thinking about your base assumptions when working on or playing a game.’

Tory Brown exploded onto the design scene earlier this year with Votes for Women, a lavishly produced and playtested game about the movement for women’s suffrage in the United States.

Placed next to This Guilty Land and even Stonewall Uprising, one might mistake it for an entirely different artifact altogether. Even the quality of the box is noticeably improved. Where its predecessors find their roots in age-old wargames, with print-on-demand publishing models and affordable components, Votes for Women heralds a more glamorous approach.

Inside the box one discovers not only a mounted board, but also heaps of wooden and cardstock pieces in three dominant colors. These denote the alignment of the game’s factions: red for Opposition, yellow and purple for Suffrage. Those two colors hint at the game’s political leanings. While Suffrage must struggle against Opposition to spread the word, garner support in Congress, and eventually vote to pass the 19th Amendment, they’re also locked in a war of ideals with their own allies.

With a background in labor organizing, Brown is no stranger to coalition-building—nor to the reality that working together to make change can mean adjusting to new voices, opinions, and even values. In Votes for Women, this materializes when Opposition plays a card to drive a wedge in the Suffrage movement. Where purple and yellow pieces were previously content to work together, suddenly one side might abandon the cause.

Brown doesn’t assign a specific value to either color, but she doesn’t hesitate to name the cause for these ideological rifts. Yes, it’s racism. While most of the country’s women agree that they want the vote, plenty of white women are afraid of their Black counterparts gaining an equal voice. Votes for Women wends its way through both sexual and racial politics, never shying away from the moral failings of the same movement it celebrates. Despite this, it never once stops being eminently playable.

‘When I started designing Votes for Women, I knew that if a slightly complex wargame about women’s history wasn’t engaging, people wouldn’t play it,’ Brown notes. ‘The game has some barriers to overcome. Getting the history just right, the tension just right, the look, the rulebook, the balance on the cards… these priorities all had to line up to thread the proverbial needle. The game brings people in with a soft hand and says, “Yay women’s rights!” and then quietly yet consistently asks them to consider race and class in an unexpected but hopefully revelatory way.’

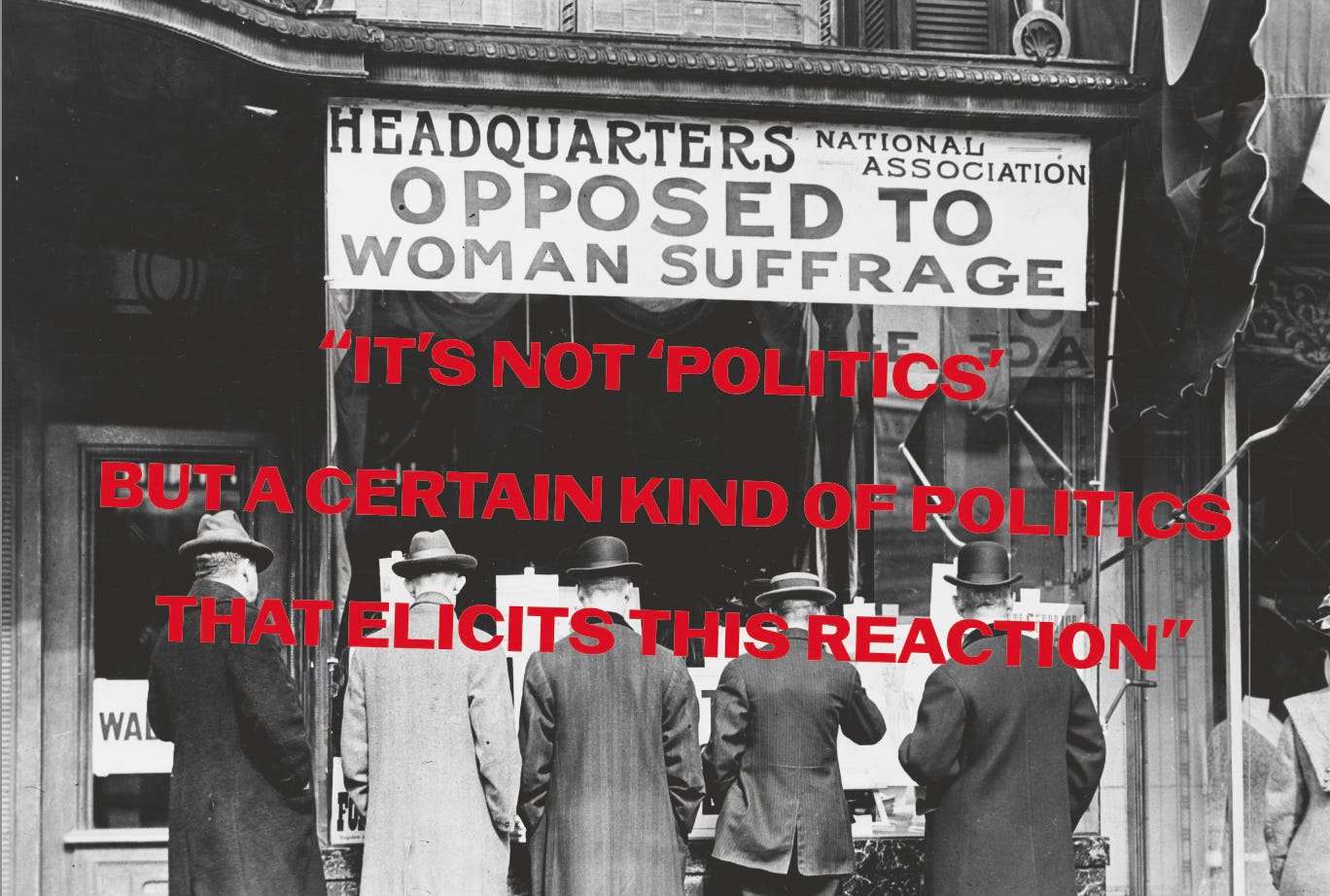

Taking on the role of Opposition is a big part of that process. As Brown puts it, ‘Some miss out on a few important lessons by never taking a chance to play Opposition. People have told me that they never thought about the fact that some women opposed suffrage, or what Prohibition had to do with suffrage, until playing the game.’

One way Votes for Women stands apart from its peers is in its portrayal of Opposition. While they’re decidedly cast as the game’s antagonist, Brown avoids taking too harsh a stance against the individuals in the opposing camp. Her goal isn’t to equate both sides, but rather to emphasize and appeal to the humanity of those who opposed women’s suffrage—and hopefully enable change today.

‘Ultimately, I hope people take what they’ve learned from my game and consider support for and opposition to social movements today. Because the baddies don’t always even question if they’re the baddies, right? Some in the opposition may in fact be persuadable. Winning hearts and minds requires meeting people where they are, and I hope Votes for Women is, at the very least, as respectful to where people who opposed suffrage were in their own historical context as it is to the people who supported it.’

Brown offers similar insights into the question of politics in games. ‘Players have all kinds of preferences when it comes to games: dice or no dice, three-hour epics or speedy thirty-minute sessions, solitaire or plays-up-to-eight. And people generally don’t say, “Keep dice out of games” or “Stick to making party games,” do they? Certain players seem to confuse their natural right to express preference with a more authoritarian might to police certain content. Because it’s not “politics” but a certain kind of politics that elicits this reaction from a small group. I think the few but loud people who say “Keep politics out of games” are demanding that we all shrink ourselves down to their very narrow, sad view of the world and of power, and doing that would make games way less fun and interesting for the rest of us.’

Fun. That’s what keeps springing to mind. Far from being miserable experiences, every one of these games is better for the inclusion of politics. They’re sharper, more invigorating, more insightful.

Whether it’s the moral clarity of This Guilty Land, the queer framing of Stonewall Uprising, or the self-examination of Votes for Women, none of these supernal titles would exist without a healthy dose of politics.

So: More of that, please.