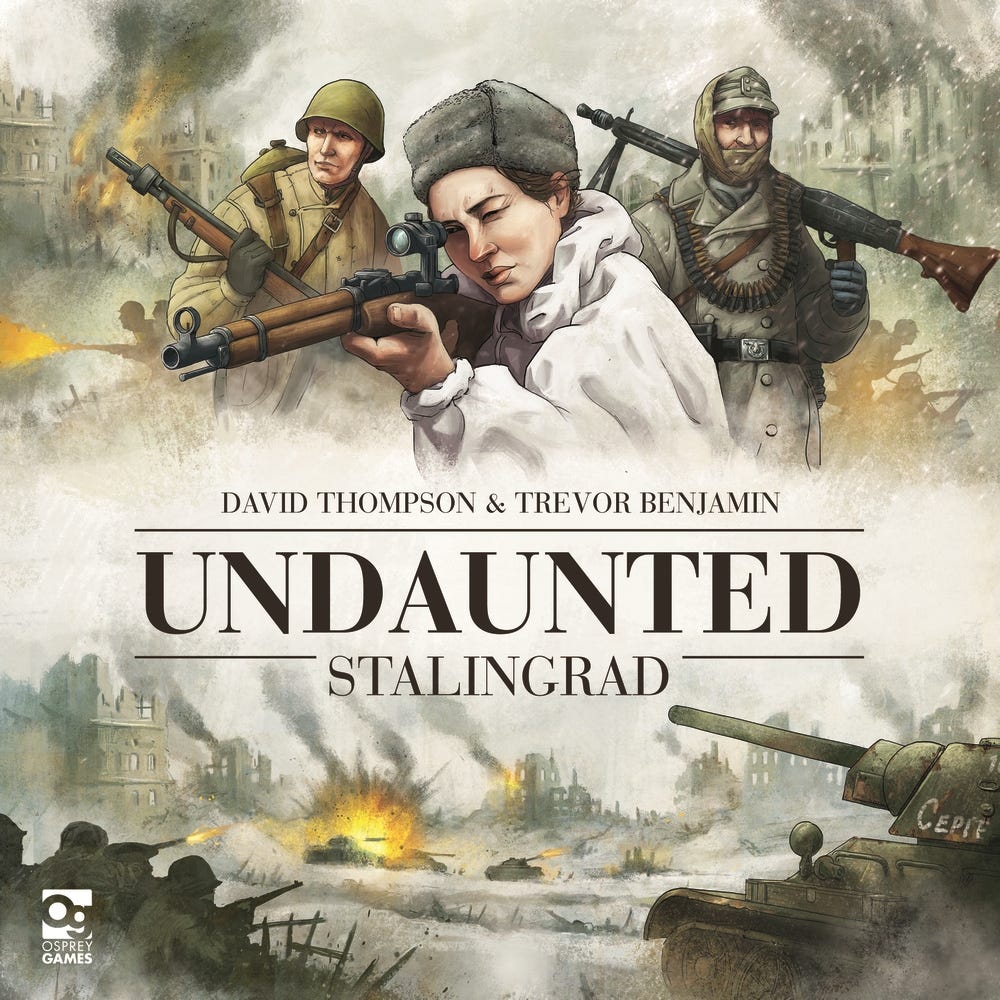

UNDAUNTED STALINGRAD

Dan Thurot casts his eye over Undaunted Stalingrad, the third game in Trevor Benjamin and David Thompson's acclaimed Undaunted series and the first to be set in World War II's brutal Eastern Front.

Ages: 14+

Players: 2

Playing Time: 45-75 minutes

Game Design: Trevor Benjamin, David Thompson

Mission Text: Robbie MacNiven

Art: Roland MacDonald

Publisher: Osprey Games

What had once been a paved street was transformed into a morass. The buildings on either side were pockmarked. One had collapsed entirely. Smoke hung in the air. The ground bristled with hastily placed mines. Fire roared on either side. Snipers and counter-snipers. Anti-tank guns sheltered by rubble. Two scarred tanks prowled forward. Squads of men darted into the open, protected only by haze. It was now or never. They would halt the Tigers or they would fall back, ceding one more city district to the invaders.

This is Undaunted: Stalingrad, the third outing of Trevor Benjamin and David Thompson’s much-acclaimed Undaunted series. It is a terror. It’s also part of a new wave of wargames that’s more interested in being approachable to newcomers than in accurately recreating every stitch of its belligerents’ uniforms.

As surprising as it may sound, the easiest point of comparison for Undaunted is Dominion, the gentle medieval kingdom-builder by Donald X. Vaccarino that introduced the world to deck-building. If you haven’t heard of a “deck-builder” before, the concept is deceptively simple. Everybody at the table begins with a starting deck of around ten cards. On your turn, you draw a portion of those cards and use them to purchase better offerings, eventually crafting a deck that can do in a single draw what would have taken three or four turns to accomplish previously.

Dominion was like coming home. There was a naturalness to its rhythms, the adding and subtracting of cards, the intensity of a well-honed deck, the little intrusions inflicted by rival players. Vaccarino’s system sparked a wildfire. The following years witnessed a thousand imitators in every conceivable setting and permutation. Most of them, to put it politely, were shameless cash-ins. For every title that earned public attention, a dozen others faded into obscurity. Eventually deck-building settled into an equilibrium, one more tool among many for aspiring designers.

By the time Benjamin and Thompson unveiled Undaunted Normandy in 2019, it wasn’t uncommon to see the deck-builder being used as the underlying system for more complex gameplay. Still, Normandy felt like a step forward. This time around, the cards in your hand personified squads of soldiers on a map, caught in another recreation of that fateful Allied invasion in June of 1944 that began the process of liberating the Third Reich’s western conquests.

Even as it retreaded all too familiar ground, Normandy’s use of deck-building gave it life. To play a card was to activate the corresponding squad —to move, to shoot, to scout deeper into enemy territory. Recruiting an additional card strengthened your presence on the map, whether by increasing how often a squad’s cards would be drawn or by introducing entirely new troops to the fray. Other cards, called “fog of war”, clogged up your deck while simulating overextended lines and enemy harassment. Your troops, meanwhile, had specialties of their own. Riflemen advanced and seized positions, gunners laid down suppression fire and snipers singled out vulnerable opponents.

When hit… Well. We’ll return to that.

For all its implied brutality, Normandy made an instant impression, earning a sequel the following year in Undaunted North Africa, which further refined the game’s scale and added vehicles to complement its infantry tactics. Above all, these titles stood out because they were so easy at the table.

Wargames have a reputation for being complex, multilayered creations, full of granular detail, sprawling orders of battle, and as much chrome as their designers can polish. Recent years have sent modern design principles and mechanisms spilling over the divide, making that reputation increasingly undeserved but in 2019 Normandy still stood out as welcoming, even among its more approachable cohort.

By 2019 nearly every hobbyist board gamer had also played a deck-builder or two. That meant hands-on training in the system’s most definable strategies. “Winnowing” is one such strategy. Since you can only ever draw a set number of cards, large decks tend to be unwieldy, spacing out desirable options over too many hands or offering the occasional worthless draw. As players of Dominion quickly discovered, a slender deck affords greater control—to such a degree, in fact, that Vaccarino hadn’t predicted just how dominant a tactic it would be to swiftly throw out as many cards as possible. Ever since, designers have struggled to rein in that impulse.

Almost without fanfare, Undaunted advanced its own solution. Adding duplicate cards—say, that of a rifleman—allows the player to activate their rifle squad more often. If that sounds obvious, that’s very much the point. Compared to some of its peers, the cards of Undaunted are downright simple. There are no conditional effects to trigger, no multi-step combos to build. Strictly speaking, having the actions printed on the cards isn’t really necessary. If the card shows a scout, its counterpart on the map behaves like a scout and has access to a scout’s roster of options.

Crucially, Benjamin and Thompson’s approach to winnowing not only furthered the simplicity of Undaunted, it also solved one of wargaming’s bigger problems: its tendency to overlook the humans staffing all those chits and markers. Evocatively illustrated by Roland MacDonald, every installment in the series has featured unique characters on every card.

The impact of this artistic decision cannot be overstated. Although every character in Normandy and North Africa is identical as a combat unit, they make themselves known as individuals as they’re recruited, both as they cycle through your hand and as they accomplish themselves in battle. I remember a particular scout in North Africa who always seemed more willing to reconnoitre the front lines and, upon being sighted, seemed especially nimble at dodging bullets.

Of course, the connection was wholly imaginary. As imaginary as a good luck charm or the game’s WW2 setting, which is to say both imaginary and as tangible as anything. That connection made me willing to take chances when that specific card—that specific face—appeared in my hand. It also made me pause, a little winded, when my scout was finally killed.

That’s how Undaunted solves the winnowing problem. When a unit suffers a hit, one of its cards is removed from your deck. This presents a constant, un-consenting winnowing, disrupting your options and crippling your battlefield strength at an unrelenting pace. Before long, you begin to feel those absences. A squad that’s been weakened and can’t act as often. A lucky scout placed off to the side of the table. Units broken entirely. Suffer enough casualties and your squads can’t recover. In some scenarios, that’s your goal: to inflict casualties until your opponent’s force can’t continue operations.

As game systems go, these losses have an affecting permanence. It’s surprising how hard it can hit. It certainly lands with more of an impact than any number of zoomed-out army chits. And that permanence is the entire foundation behind Stalingrad.

Permanence is the watchword of legacy games, the concept that broke onto the scene with Rob Daviau’s Risk Legacy, in which stickers were applied to the board, markers inked the names of cities, and cards were torn in half to ensure they would never appear again. Stalingrad offers a gentler legacy. There’s nothing preventing its players from resetting that benighted city and its doomed armies. It’s almost a relief, being able to turn back the clock.

Until then, however, Benjamin and Thompson have crafted one of the most gut-wrenching board games of the past few years. The core appeal of Undaunted is secure, right down to the ten-sided dice that clatter across the table to determine whether a volley of suppression fire has taken its intended effect. Those bullets and shells take an even greater toll than before.

Across fifteen sessions, squads are transformed into ragtag bands. Surviving troops gradually become veterans, earning fresh cards with little perks: a rifleman who’s learned to handle room-clearing grenades, a scout who can escort fellow soldiers through treacherous terrain, gunners with the ability to suppress wider areas.

Unfortunately, the inverse is also true. Throughout the game’s branching campaign, it isn’t uncommon to find oneself standing at the intersection of a dilemma. An objective has been designated. To seize it, you must navigate a killing field. Is it worth the sacrifice in manpower? Which of your troops will you hurl into the crossfire?

Those sacrifices, you know, will have lasting effects. In this case, squads aren’t eliminated altogether. Instead, fresh troops and veterans alike are reduced to tattered bands. Now your rifle squad wields pistols and spades, your scouts limp rather than darting around corners, and your gunners are barely able to reposition.

In the process, something noteworthy happens. Where Normandy and North Africa put the faces of its soldiers front and center, Stalingrad resorts to an even harsher measure by stealing them away forever. Once-fresh troops become bandaged and broken. The city itself is shattered, structures cast down to rubble. Even veterans aren’t immune, their appearance in the casualty pile doubly tragic. Those were known faces with cultivated abilities. All gone.

At the same time, there’s an undeniable arc to these proceedings. New squads and eventually vehicles are introduced. Even your squad leaders, abstracted in the sense that they never appear personally on the map, may find themselves touched by the conflict.

After a handful of skirmishes, bombardments and new piles of sandbags have transformed the city entirely. In this light, Stalingrad’s occupants begin to resemble shades and revenants, locked in an eternal struggle to command the ossuary. Despite being a game about composing squads, executing bold maneuvers, and rolling well, its sense of horror is undeniable.

François Truffaut famously noted that there was no such thing as an anti-war film. Wargames have always grappled with a certain discomfort. Namely, that these are horrors and playthings alike. Stalingrad leans closer to the latter, but it exhibits an admirable dedication to not shying away from war’s consequences. The result is adrenal in the firefight but sobering once the battle’s done.

Once the bodies are stacked and the ruined map is put away, it lingers in the thoughts. Undaunted Stalingrad is a masterpiece.

Dan Thurot is probably best known for his writing on board games, most of which you can find at his site Space-Biff! However, he'd rather be known for being a good dad to his two daughters, a quieter but far more worthy accomplishment

This review originally appeared in Wyrd Science Issue 4